Morton Feldman and the Memory of Art

On Feldman's String Quartet II

“Because the best music is strong and guides and cleanses and is life itself.”

- Lester Bangs

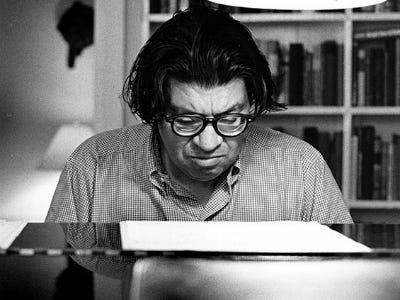

Morton Feldman’s outward persona was a projection, a contradictory mirage of sharply intellectual aphorisms and easy-going joie de vivre housed in the body of a very large man. Christian Wolff writes:

“He talked wonderfully, sharply, outrageously, but that wasn’t quite his music. One thinks of the disparity of his large, strong presence and the delicate, hypersoft music, but in fact he too was, among other things, full of tenderness and the music is, among other things, as tough as nails.”

Morton Feldman’s String Quartet II (1983) confronts you with five hours of soft, sparse gestures that don’t care about you or anyone else. If they’re heard for long enough, they start to sound like calm, like joy, like fear, like pain. For Feldman, art is a metaphor for life, and with its length and consistency his String Quartet II attempts to encapsulate the whole.

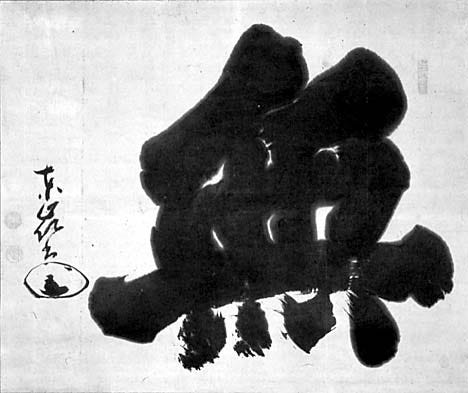

The repetitive, back-and-forth rhythms, the ghostly breaths of string harmonics, and the indecipherable plucks that make up Feldman’s score are simple to the extreme. Indeed, the musical and aesthetic concepts so vigorously proselytized by Feldman in the 60’s and 70’s — that the composer must let go of the idea that sound can be precisely controlled and contained, that sound should, in some almost Platonic sense, be allowed to exist purely as itself — have roots in Zen, a practice in which simple occurrences take on existential significance. Feldman’s philosophical stance aimed at the freeing of sounds from their referents within the bounds of a proscribed system. Only then, according to Feldman, would sounds be free to reveal their inherent mystery: where does sound come from, and where does it go? Where does silence end and sound begin? Much as the simple task of observing one’s breath can open the door to profound reflection, the music of Feldman’s late period asks us to stare intently at sound until we respond to it outside of harmony, pitch relationships, instrumentation, and music history. In both Zen and in Feldman, the simple becomes complex when focused on intently and when looked at from every possible angle.

“What music rhapsodizes in today’s ‘cool’ language”, Feldman wrote in the early 70’s, “is its own construction.” Whether it be figuration in painting or tonality, serialism, and other procrustean beds in music, technical laws and processes are for Feldman mere frames housing something we would do well to simply let be, something we must allow to come into being intuitively. In an interview given towards the end of his life, Feldman quotes Debussy, saying: “Every work of art develops a law. But you don’t begin with it.” It was these artistic laws, whether inherited or self-created, which Feldman attempted to free himself from throughout the years.

Thus Feldman’s String Quartet II gives us no logic but its own, winding through hours of duration propelled only by its own delicate momentum. Glimmers of consonance come and quickly dissipate: there seems to be no conception of tension and release, no sense of building and decaying, no sense of progress and arrival. The music that occurs exists in that moment only, even if repeated: what note sounds the exact same way each time, what string vibrates exactly at pitch? Here, consonance is not happy or upbeat, dissonance is not harsh or unsettled. Events happen: who is to say whether they are “good” or “bad”?

Still, music as harmony and rhythm, as form and content, carries over into even this landscape. The ideal musical world of sounds-in-themselves is unrealizable: we simply have heard too much, have lived too much to respond with a fully blank slate. In Feldman’s later writings and interviews, memory takes on a greater and greater role: the relation of aphoristic anecdotes akin to Zen koans, jocular reflections on musical colleagues — the aging composer seems to be opening up, to be convincing himself of his fading attachment to the happenings of the past and the prospects of the future.

Musical memory, too, is an increasing preoccupation — the pieces we’ve heard, the music we’ve loved and which now leaves us, if not indifferent, then at least ambivalent. “I do in a sense mourn something that has to do with, say, Schubert leaving me”, writes Feldman. “Also I really don’t feel that it’s all necessary anymore. And so what I tried to bring into my music are just very few essential things that I need. So I at least keep it going for a little while more.” Trying and failing to bring the past into the present, its meaning intact, is a theme of Feldman’s late work. His strategy is to distill: to clarify and prune until, as in the work of Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, only the lithe, rugged, and inscrutable essentials remain. How else are we to interpret Feldman’s slightly earlier work for solo piano, Triadic Memories (1981), than as a sort of requiem for the musical meaning of the past, as a eulogy for functional harmony and artistic self-expression?

On skimming Feldman’s writings as collected in Give My Regards to Eighth Street (Exact Change, 2004) one may be forgiven for thinking it a book of contemporary art criticism rather than an anthology of missives from the musical avant-garde. References to the work of friends and interlocutors from the nightly crowd at New York’s now shuttered Cedar Tavern dot its pages, most prominent among which are the painters Philip Guston and Mark Rothko, who’s aesthetics and artistic practices seem to have done more for Feldman’s own thinking than any of his musical contemporaries (barring Cage). Many have compared Feldman’s monolithic later works to Rothko’s color field paintings, a connection brought on, to be sure, by the relative scale of each when compared to the artistically accepted and practical norms of their time.

The impracticality of working at such a scale, the almost inevitable alienation which occurs between Feldman and his potential listeners when they are confronted with such a time commitment — Feldman must have known these things and accepted them as necessary. Yet he worked intuitively, without a system, feeling his way through a work until somehow all its pieces were in the right place. Or rather, until each small unit of repetition could stand alone from the whole yet simultaneously resonate across minutes and hours.

At roughly the fifty minute mark of String Quartet II, a beautiful chorale, an alternation of just a few notes by each player, emerges just long enough to throw the whole piece, the whole project, into question. How can we go on through the piece knowing that this moment of grace might never return, that it is, in reality, just another combination of sounds, neither arrived at nor departed? There is no build-to nor fade-away from this moment, no context in which to understand it in any way other than intuitively, emotionally. Although this chorale never returns, one can’t help but search for (and find) it in the coming hours as little snippets of a lost space that is forever in the past.

Despite his fixation on the artists and thinkers of the past — Cezanne and Webern, Kierkegaard and Tolstoy — Feldman wrote that he and the other artists in the New York of the 50’s and 60’s were able to do what they did through a lack of concern for history, a not entirely articulated disregard for a linear sense of what had been done before and what would be done after. “What was great about the fifties”, he writes, “is that for one brief moment — maybe, say, six weeks — nobody understood art. That’s why it all happened.”

If other music rhapsodizes its own construction, its own rigorous history and the formalism of its pedigree, Feldman’s music rhapsodizes, among other things, a space of one’s own, the enigmatic solitude that can appear, if we let it, even in a crowd, even in a concert hall. One sits down at the page, and suddenly one is existing. Given enough time, given enough space, given enough insistence.…

A certain esoteric-ism is at the heart of much of Feldman’s work, and this only becomes clearer as he shifts to larger, monolithic works of extreme duration and of extreme sparsity. In his essay “Niether/Nor” Feldman writes: “if art must be Messianic, then I prefer my way — the insistence on the right to be esoteric. I confess to the fact that whatever describable beauties may arise from this esoteric art have always been useless.”

Feldman’s String Quartet II celebrates solitude and an almost Zen sense of being present. It also expresses something of an artistic spirituality that relies, as concepts of the sacred often do, on the setting of something apart from the world: art as something non-functional that is at a remove, via a stage or a gallery wall, from “everyday” concerns. Feldman is interested, not in what art can do in relation to the “social world”, but in Art itself, its internal problems and paradoxes, the power of its isolation. In some ultimate way Feldman is a proponent of Art for Art’s sake: he would like to distill the impulses that have shaped the art of the past down to their very essences, to present them at a remove from names, places, times, and titles. Yet, in purely material terms, this project has no purpose, and serves to further nothing but Art itself.

For things to be simple: what else could we want? For things to be clear, and thereby, if not quite meaningful, then at least truthful. In Feldman’s words from a 1982 lecture: “Do we have anything in music for example that really wipes everything out? That just cleans everything away?” Only through long-exposure, only through a sustained alienation from form and function, from the everyday and the contextual, can the slate be wiped momentarily clean. That it fills again almost instantly is of no consequence to the present.

“What good does it do, when I play the game everything changes, doesn’t it? Everything changes.”