"The world is a great cowshed which is not so easy to clear out as the Augean stable because, while it is being swept, the oxen stay inside and continually pile up more dung."

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856)1

Hollywood was a soulless place, but not without its charms. In the 1940’s, it was still, in the words of Eisler biographer Albrecht Betz, “the ‘glamorous’ Hollywood of the star cult, the glittering revues with big bands in the background and the pretentious extravaganzas that provided millions of anonymous film-goers with models for the dreams of their waking hours.”2 For a generation of German directors, actors, writers, and composers who settled nearby in the hills of West LA, Hollywood was a refuge from the war and a chance to work with an eye towards a global audience. But it was also a strange and foreign place, one in which artists had to play by unfamiliar rules.

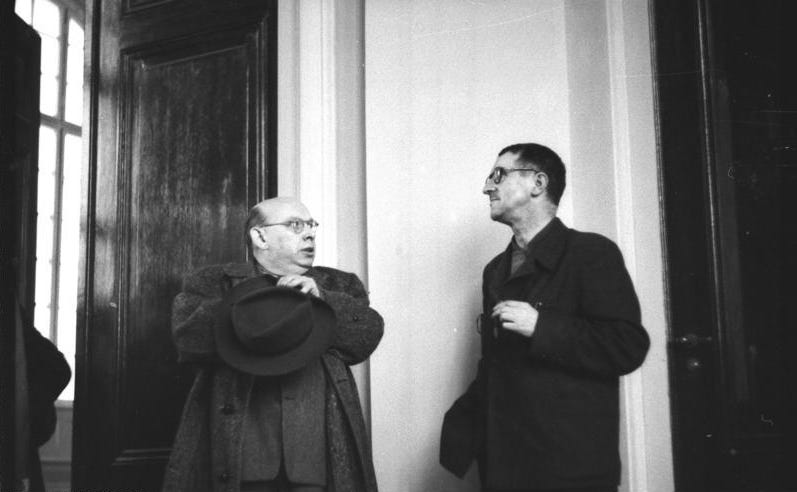

The unusual concentration of German ‘great names’ who found their way to Los Angeles in the 1940’s — Thomas Mann, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Bruno Walter, and Max Reinhardt, among others — got along as well as you’d expect: egos flared, cliques were formed, and old feuds were rekindled. It was in the air: for many, reaching out for material success in such a cynical, profit-driven, and hollow artistic world felt like a devil’s bargain, one in which the newly-minted Americans were forced to sacrifice their artistic integrity at the altar of the American Dream. Still, the stability offered by the steady churn of big-budget films was difficult to resist after the traumas of war and flight. For Brecht, Hollywood was “the center of the international narcotics trade”3, a place riddled with capitalist greed and capitalist art. “When I see Eisler”, he wrote, “ it is a bit as if I am stumbling around muddle-headedly in some crowd and suddenly hear my old name called.”4

Eisler arrived in Hollywood in 1942, having left Germany for Vienna in ‘33, just in the nick of time. After an initial period of uncertainty in his erstwhile hometown, he lived an increasingly itinerant life in exile, finding work in Czechoslovakia, Paris, London, Denmark, Republican Spain, and the United States, which he first visited for a lecture and concert tour in 1935. His initial impressions were of a country full of contradictions and without the guile to hide them:

“… this country is really magnificent, because here there is a great lack of superstructure. Here class opposes class in an extremely naked way and the struggle takes on the most extreme forms of brutality. That is a refreshing feature. And further there is this splendid pragmatism even though theory is not entirely lacking.”5

As the pockets of space he had made for himself in Europe began to shrink, Eisler, like many central-European intellectuals, found the United States to be an attractive escape option: far from the war, in search of a more ‘refined’ culture, and with the piles of cash to pay for it. In 1938 he made his way to New York, and after overcoming a series of bureaucratic hurdles involving a flurry of visa applications and expirations (as well as an extended sojourn in Mexico City), he was finally allowed to stay.

Having secured his spot in the heart of capitalist empire, Eisler was immediately faced with the dilemma that would shape his work and thought in the years to come. It seemed the only way to make it in America was to keep his political sentiments under wraps and to turn to film scores for his bread and butter. Divorced from the community of workers choirs, public schools, and revolutionary theaters which had allowed him to truly integrate his art with his politics, the constant threat of deportation precluded any attempt to make political contacts in his adopted country. What then for ‘applied music’?

There was one consolation, at least: on his arrival in California, Eisler was reunited with his longtime friend and comrade Bertold Brecht, who had landed in Hollywood in 1941 after a similarly circuitous route through Denmark, Stockholm, and Helsinki. One of Eisler's best-known collection of works, the Hollywood Song Book, stems from this period, a massive collection of songs for piano and voice in which Brecht's poetry features prominently. Settings of Brecht’s “Hollywood Elegies”6 form the core of the collection, a series of short stanzas which attempt to grasp the remoteness and isolation which characterized the émigré life in wartime Hollywood:

"Under the long green hair of pepper trees, The writers and composers work the street. Bach's new score is crumpled in his pocket, Dante sways his ass-cheeks to the beat. The city is named for the angels, And its angels are easy to find. They give off a lubricant odor, Their eyes are mascara-lined; At night you can see them inserting Gold-plated diaphrams; For breakfast they gather at poolside Where screenwriters feed and swim. "Every day, I go to earn my bread In the exchange where lies are marketed, Hoping my own lies will attract a bid."

Another outcome of Eisler’s stay in Hollywood was a reconciliation with his old teacher Schoenberg, who had secured a teaching position nearby at UCLA in 1935. A frequent guest at Eisler’s house in the Pacific Palisades, Schoenberg seems to have gradually retaken his place in Eisler’s thought as the ideal composer, at least where craft and artistry were concerned. Like his teacher had done in his early career, Eisler took to composing chamber music in the 1940’s, going so far as to use the iconic instrumentation of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire (1912) and an anagram of his teacher’s name for the chamber work Vierzehn Arten, den Regen zu beschreiben (Fourteen Ways of Describing Rain). In a lecture on Schoenberg given towards the end of his life, Eisler summed up his later feelings towards his mentor and his music: “The decline and fall of the bourgeoisie, certainly. But what a sunset!”7

Eisler’s Hollywood works turn increasingly towards the past, the personal, the poetic, and the subjective. Although “Hollywood Elegies” clearly expresses disgust at the commercialism and vanity of Los Angeles, it also makes clear that Eisler, Brecht, and their fellow artists were complicit in this rat race, just a series of crabs among the many struggling towards the bucket’s rim. It goes without saying that both the insular poeticism of his chamber works and the defeated cynicism “Hollywood Elegies” settings bear little resemblance to the fight songs and agitprop of Eisler’s youth.

The intense inequality on display in 1940’s Los Angeles, the destruction of the worker’s movement in war-torn central Europe, and the increasing brutality of the Stalin regime during this period would have led even the most die-hard communist to question their faith. The revolution that had seemed so imminent in 1920’s Berlin had never arrived, and the shining example that the Russian Revolution had provided for workers and intellectuals alike was clouded by reports of disappearances and severe censorship from within what was supposed to be a worker’s paradise. We can’t be too hard on Eisler: without officially renouncing the fight for a better world, it is relatively easy to slip away from the front lines, let life move on, and allow disappointment to become nostalgia, cynicism, and inaction. After all, staying on the barricades indefinitely is bound to get you killed, imprisoned, or worse.

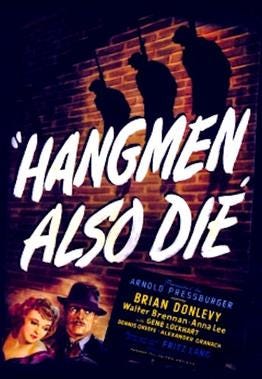

Seen in a more charitable light, Eisler’s work in Hollywood and his fixation on film can be seen as attempts to put the values that motivated his initial infatuation with communism to use in a new technological and cultural context. Not all of his film scores of the period were cash grabs: one of his most famous scores was for Hangmen Also Die! a 1943 film loosely based on the recent assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, chief architect of the Holocaust (Brecht provided the project with his only script written for a Hollywood film). Was this full-throated communist propaganda aimed at teaching the working class how to think dialectically? No. Was it arguably more politically effective?

Quite possibly.

In preparation for a lecture given in Prague soon after his deportation from the United States, Eisler highlighted a single sentence in his notes which may as well serve as his revised artistic manifesto: “What should be striven for is a style capable of combining the highest artistry, originality, and quality with the greatest popularity.”8 In the most sympathetic interpretation of Eisler's later work, he remained a diehard communist throughout his sojourn in the United States. Only his strategy had changed: rather than agitating for abrupt and implicitly violent seizures of power, the goal was to use the latest technology to broaden the artistic and political horizons of 'the masses', thereby Trojan-horsing critiques of life under capitalism into the very heart of popular entertainment. Given capitalism's well-documented ability to absorb and resell any insults hurled at it, it goes without saying that the success of this strategy was limited. The vote is still out on whether Oscar-nominated anti-fascism is effective in anything but an abstract sense.

Eisler is a figure of immense interest to me, although I don’t much care for his music (or in many cases, his politics). As a fellow critic, Eisler’s early writings as music critic for the communist rag Die Rohte Fahne show off a satirical bent and a wit that is hilariously harsh, yet pointedly analytical. You get the impression that this little cue ball of a man was easy to underestimate and deadly to argue against. With all the manners of an erstwhile bourgeois, he would offer you some schnapps and a wry smile as the dust settled, the conversation quickly and politely turning to contemporary literature or the latest opera by Ernst Krenek. Although I am far from a Marxist-Lenninist, Eisler’s ideas about music and its place in the world reflect many of my own worries as a classically trained musician, and the isolationist, elitist rhetoric of the ‘art for art’s sake’ crowd remains alive and well in our time. More importantly, the ideal for which communism was Eisler’s vehicle still rings true to my ears: “An art which loses its sense of community thereby loses itself.” That Eisler, like so many others, was carried away by the tide of ‘scientific socialism’ in the early 20th century cannot be an excuse to throw the baby out with the bath water.

The central problem that Eisler wrestled was that of the 'artist in society'. How to reconcile the “necessary laziness"9 of poets, the myth of isolation and genius which surround artists in Western culture, with the need for communal action and solidarity? “In the real world", writes Julian Silverman, the sort of "ridiculous self importance, vanity and simple-mindedness" which attends many fledgling poets and political firebrands alike "can cause the death of millions." Even still, "in the world of the imagination, these same unforgivable vices are perhaps even necessary qualities for the creation of visions which can haunt us for centuries.”10

After the U.S. showed him the door in 1948, Eisler returned to Germany, or rather, the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (East Germany), for which he composed the national anthem, “Auferstanden aus Ruinen” (Risen from Ruins). With this patriotic, march-like song he was back in the saddle, trying to conjure socialism into the world via rousing choruses and exuberant flag-waving. Yet he quickly found that the nominally communist East German government had little appetite for new music, and little tolerance for innovation. In Johannes Faustus, Eisler’s opera from the period which earned him the ire of the East German establishment, Silverman sees a thinnly veiled autobiography wrapped in German myth:

“Eisler makes his Faust a follower of Luther in his betrayal of the peasants, and an opponent of the revolutionary Müntzer, their consistent defender. He becomes an artist, goes to ‘Atlanta’ and performs all sorts of public magical fantastical artistical feats, not returning to German for 12 years. Back home, he shows off the gold and new arts from Atlanta, and is justifiably damned.”11

By 1953 the itinerant composer was back in Vienna, an exile from the only nominally socialist German state ever to exist. Eisler was on the go once more.

Heinrich Heine, Sämtliche Werke, ed. E. Elster, Leipzig, Berlin and Vienna 18878-90, vol. VII, p. 409. Quoted from Betz, Albrecht., and Bill Hopkins. Hanns Eisler, Political Musician. Translated by Bill Hopkins. English edition. Cambridge [England] ;: Cambridge University Press, 1982: pp. 246.

Betz, Albrecht., and Bill Hopkins. Hanns Eisler, Political Musician. Translated by Bill Hopkins. English edition. Cambridge [England] ;: Cambridge University Press, 1982: pp. 183.

From Brecht’s Arbeitsjournal as published in Brecht, Bertolt, Gesammelte Werke, Frankfurt am Main 1967.Quoted from Betz, 184.

Brecht’s Arbeitsjournal, pp. 422. Quoted from Betz, 185.

Letter from New York of 19 January 1935, Hanns Eisler Archive, Berlin. Quoted from Betz, 143.

The excerpt used here is of the first three stanzas in a translation from the German by Adam Kirsch. The full poem can be found here.

From Hanns Eisler, Materialien zu einer Dialektik der Musik, Reclam, Leipzig 1973. Quoted from Betz, 228.

From a note on a single sheet in the Hanns Eisler Archive, Berlin. Quoted from Betz, 209.

Cribbed from T.S. Eliot’s famous 1919 essay -

Julian Silverman. “‘Only a Composer’: Reflections on the Eisler Centenary.” Tempo, no. 206 (1998): 28.

Silverman, 27.