On December 11th, 1981 the composer Terry Jennings was robbed, beaten, and left for dead in San Pablo, California. Friends and family were informed that a drug deal had gone awry, and that, as they had so often predicted, Jennings’ years-long addiction to heroin had finally caught up with him. His broken skull and his senseless death, it seemed, were simply a result of poor choices, of a disregard for the workings of the world that led him to keep “unsavory” company and to shun treatment for his addiction. Yet one could argue that Jennings had, long before his death, been lost to life, that he had consistently shown no signs of ambition or drive in his musical career or his social interactions. Indeed, he was seemingly compelled by a different logic, one that proved difficult to communicate. In the words of Brett Boutwell, he was “a bobbing cork impelled by stronger currents.”1

Jennings’ musical life began promisingly. According to Boutwell, “he arranged Stravinsky for his junior high school orchestra, practiced Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes by his mother’s side as a twelve-year-old, and once participated in an impromptu professional rehearsal of Schoenberg’s Septet, op. 29, at the Los Angeles Conservatory, transposing the E-flat clarinet part at sight.”2 Alongside his longtime friends Dennis Johnson and La Monte Young, Jennings helped form the early core of the minimalist movement, a lasting aesthetic paradigm that would shape the landscape of American composition for decades to come. Jennings was an integral part of minimalism’s aesthetic and conceptual origins, an obscure and largely uncelebrated figure who’s death nevertheless marked something like the end for the sparseness of material, compressed scale, and air of reflection which characterized early minimalism.

While the term is associated today with its biggest names — Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass — the aesthetic priorities explored by Johnson, Young, and Jennings in the late 50’s more accurately deserve the title of minimalism. Young’s 1958 Trio for Strings, regarded as a seminal work in the mythos of the movement, is full of sustained single notes, and its unblinking obsession with long-tones requires a radical reorientation in time. Johnson’s November, only recently reconstructed by the musicologist Kyle Gann from an aging cassette tape, is an exercise in cells of musical material extended over hours of semi-improvised, quiet piano harmonies. Johnson, Young, and Jennings would go on to influence Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Alvin Lucier, and the numerous other composers who crafted this new wellspring of American music into an international phenomenon, with works like Riley’s 1964 In C and Reich’s 1976 Music for 18 Musicians becoming standard repertoire for ensembles worldwide. These later minimalist works are much more grandiose, featuring larger instrumentation and a denser harmonic pallete, yet the work of Riley and Reich nevertheless shares with that of Young and Jennings a preoccupation with simple processes, material, and forms which yield complex, sometimes unexpected results.

The only readily accessible collection of Jennings’ work is contained on John Tilbury’s album Lost Daylight, a release full of quiet piano works all under ten minutes long. These five works, written between 1958 and 1965, play with serialism, tonality, modes, and improvisation in a highly idiosyncratic manner. Jennings’ Piano Piece of 1958 adapts serialist techniques of pitch organization, in a method borrowed from Young, to a new context focused on sustained tones, yet Jennings’ approach is compressed and contracted into a tight, Webern-ian four minutes. Equally brief and, in Tilbury’s realization, full of long silences, Jennings’ Piano Piece of 1960 distills the harmonic language of 12-tone composition into an almost improvisatory exercise, taking the spirit if not the exact form of Webern’s pointillistic serialism and freeing it from its organizational confines. Jennings is consistently freer in his use of compositional forms and processes than Young, and his work for solo piano is quietly, unremittingly, and unblinkingly self reflective.

These are works, it often seems, meant for Jennings and Jennings alone. As such, Jennings’ piano pieces beg the question: were these outward-facing gestures? Were they meant for the consumption of critics, composers, and historians alike? Could Jennings have had an audience in mind for these works? Could he have written them intending to communicate something?

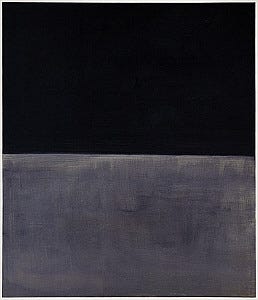

The symbolic transaction between a speaking artist and a receiving audience, so integral to Western visions of artistic practice, is what is troubling in relation to Jennings’ music. The difficulty of communication was also a recurring theme of his life: by all accounts, he was highly intelligent yet diffident to a fault, and when listening to a piece like Winter Sun, this reticience is made palpable. Although Jennings is clearly “saying” something here, it is not a message meant for easy interpretation, and it is by no means a lengthy sermon. Winter Sun and Winter Trees were both written around 1965, when Jennings and his family were staying in a desert commune among a restrictive Arizona religious order known as the “Children of Light”. Thus these tender pieces still bear, in their titles and in their cold harmonic light, the marks of a desert isolation. In a social sphere in which a musical communion with the sun and trees might have insulated Jennings from the oddities of commune life, the composer found a way of “speaking” that was clear and simple yet metaphorically dense.

Still, the earlier example from 1960 of For Christine Jennings shows evidence of a more concrete audience in its dedication to Jennings’ little sister. What he could have wanted to say to her with such a delicate yet tightly wound piece is difficult to tell. In the hands of John Tilbury the piece is a measured layering of slowly dying notes, building gently into small flourishes of activity and dissipating into suspended, ambiguous chords. Jennings’ use of notes without stems, such that their exact duration and rhythmic relationship is up to the performer, allows for a distilled and well-crafted play of harmonic color to retain the feeling of improvisation. Traces of serialism can still be heard in this work, but its harmonic language owes more to jazz than to the expressionism of the Second Viennese School. Still, what is striking about For Christine Jennings is that, in spite of its clear precedents and influences, the music feels as if it were arrived at intuitively, having been filtered through a highly personal series of aesthetic or even spiritual prerequisites until it was left as a shining core. In Jennings’ music, it is not the compositional process or the constraints of style which come to the fore, but the quiet shifts of timbre and color of each note, of each harmony, and of each silence.

In For Christine Jennings one finds a message meant very concretely for one person, not a declaration of artistic intent or genius meant for the appreciation of an expectant crowd. Yet there were those for whom, during Jennings’ lifetime, these and other works nevertheless resonated deeply. Among them, one has to assume, was La Monte Young, who’s work of the late 50’s and 60’s shares many aesthetic priorities with that of Jennings. In the years following Jennings’ death and in the few pieces of writing about his work, Young has often been positioned as something of a mentor to Jennings, a musical guru who took his younger friend under his wing and, it is implied, supplied the composer with many of his ideas and techniques. Young himself has done little to dispel this illusion, and in fact has maintained, through his organization the Mela Foundation, a tight grip on the rights for the performance and dissemination of Jennings’ work. Any performances of his music must be done through Young and his foundation, as has been the case in Charles Curtis’ recording of his work for Cello and Piano titled Song and Quator Bozzini’s public performances of his String Quartet, such that Jennings’ work is rarely heard and little known. For the upcoming release by Saltern Records of Jennings’ 1960 Piece for Cello and Saxophone, Young has gone so far as to rearrange the work in just intonation, reworking Jennings’ piece posthumously much as he regularly does with his own works.

Jennings seemingly did not seek out an audience, did not, as artists are often expected to do, feel the need to project himself outwards into the world in search of fame, glory, or money. To create anything requires a certain kind of faith: sometimes this is a faith in ones ultimate artistic triumph, but it might simply be a faith in one’s ultimate financial stability. For an artist, the object, process, or other aesthetic experience being brought into being over hours of reflection and work necessitates a belief that the work should and can exist or take place. For La Monte Young, this faith seems to be centered around his own ego. He thus encapsulates the unfortunate ways in which faith in oneself and one’s work can turn the artist into an posed statue, a cultivator of image who must battle with others for the attentions of posterity.

What is paradoxical and, I would argue, so enchanting about Jennings’ piano works is that they seem to have been created for no outward reason, for no reason having to do with anyone other than Jennings and the people closest to him. Given their sparsity, brevity, and evident lack of wholehearted allegiance to any preexisting musical trend or technique, they could not have been aimed at advancing Jennings’ career. Indeed, as Jennings stole time to improvise and write in his desert commune, he may never have known whether these works would find an audience larger than himself and his close family. Yet it is the elegance and compression of Jennings’ creations that give them their emotional potency, a restraint that shows signs of a different kind of faith. It is the purposeful smallness of Jennings’ gestures towards family and friends, towards the sun and trees, that give these works an intimacy and, ultimately, a spiritual charge which no grand artistic statement can ever attain.

Boutwell, Brett. “Terry Jennings, the Lost Minimalist.” American Music 32, no. 1 (2014): 99.

Boutwell, 85.